St. Louis Cemeteries

Introduction

Finding Guide was developed to assist researchers in locating cemeteries in the city and county of St. Louis, Missouri.

An alphabetical index to all cemeteries found in St. Louis City and County is provided as well as denomination-by-denomination listings. Each St. Louis Cemetery is recorded using the same format:

Alphabetical Index

The column labeled "SLGS Cemetery Volume" refers to "Old Cemeteries, St. Louis County, MO" located in print at call no. R 977.865 O44. Cemetery records on microfilm are indicated by a film number listed under the column heading "Microfilm / Microfiche No." and are filed by number in microfilm cabinets in the History and Genealogy Department.

Besides the items listed, we have cemetery indexes and abstracts in print for many localities. Check the library catalog for availability.

The four earliest Protestant burial grounds in St. Louis city and county are Baptist, Methodist, and (Southern) Presbyterian. Germans arriving in the late 1830s expanded upon this number with the proliferation of German Evangelical, Evangelical Lutheran, and Lutheran congregations.

Protestant Churchyards

The oldest protestant churchyard in St. Louis County was established by Fee Fee Baptist Church in 1814. Protestant Churchyards were common in both St. Louis City and County. Many congregations established a churchyard on the land neighboring the church building. The churchyard belonged to and was maintained by the congregation. Protestant Churchyards followed a formal, geometric pattern in landscaping and in their burials. Headstones were placed in straight north - south rows with text facing east. Any roads were straight and entered to the center and around the exterior of the yard. Churchyards did not contain family plots. Typically burials occurred one right after another - with the exception of the occasional spouse buried next to one another. Landscaping followed the simple pattern with trees specifically selected for their simplicity (mostly Oaks and Cedars). A sexton maintains the churchyard.

Rural Protestant Cemeteries

Following the St. Louis cholera epidemic of 1849, Protestant Churches adopted the practices of the rural cemetery movement when designing their burial grounds. In 1855, German Evangelicals designed the first Rural Protestant Cemetery in St. Louis County - St. Peter's Cemetery on Lucas & Hunt Rd. While established and maintained by congregations, these rural cemeteries were built in the county and abandoned the geometric simplicity of the churchyard design. The Rural Protestant Cemeteries were often designed by civil or landscape engineers and featured rolling hills, trees, and family monuments. Burial plots were sold in family lots, similar to their rural cemetery counterparts. Many of these cemeteries later established an endowment for perpetual care - and have been well maintained due to this reason.

Cemeteries Associated with Specific Denominations:

German Evangelical Cemeteries in St. Louis

This guide provides information about cemeteries related to congregations of the former Evangelical Synod of North America located in St. Louis City and County. The Evangelical Synod was a German Protestant denomination that in the course of several mergers has been incorporated into the present-day United Church of Christ. The guide was compiled by the staff of the Eden Theological Seminary Archives and is made available here by permission. Records for some cemeteries listed in the guide are available on microfilm copies in the St. Louis County Library History & Genealogy Department.

A guide to German Evangelical Synod congregations in St. Louis is also available.

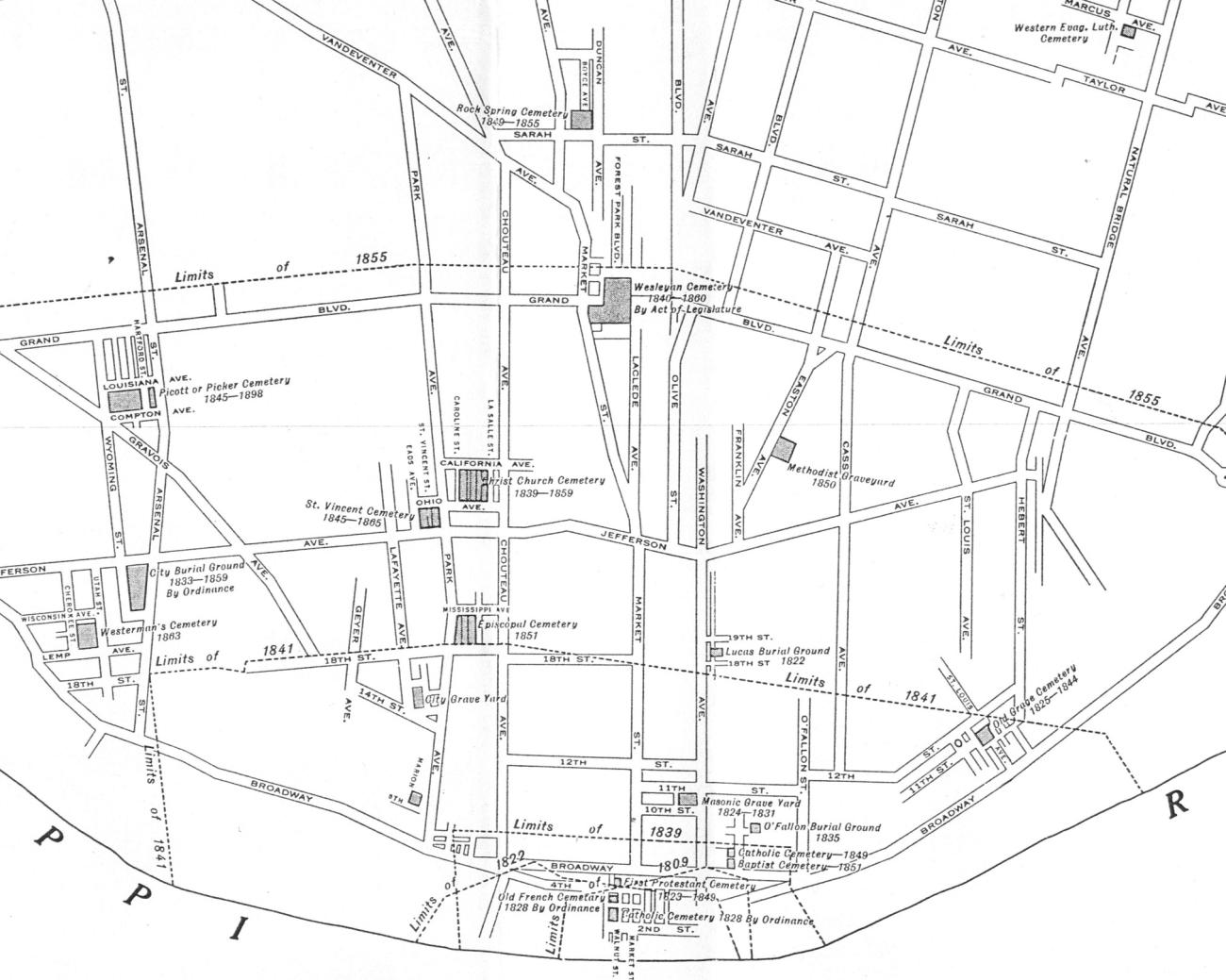

Early Cemeteries

The first Jewish cemeteries in St. Louis were United Hebrew (Jefferson and Chouteau) and Camp Spring (Pratte street between Gratiot and Cooper) which were located in the area of the Mill Creek Valley train yard. These cemeteries were established in the 1840s as places for Orthodox Jewish burials. As with so many city cemeteries, the 1849 St. Louis Cholera epidemic filled the cemeteries rapidly and both groups had to establish new cemeteries in the county.

County Cemeteries

Emanu El est. Mount Sinai Cemetery on Gravois Road in 1850 and transferred bodies there from Camp Spring in 1872. United Hebrew est. a new cemetery in 1855 on Canton Ave. in what is today University City. United Hebrew transferred bodies from the city in 1880. Both congregations began to lean towards reform Judaism and in 1871, Sheerith Israel Congregation opened B'nai Amoona Orthodox cemetery at North and South Road.

Eventually Mt. Sinai changed it's name to New Mt. Sinai. The Mt. Sinai and United Hebrew cemeteries adopted a rural cemetery movement approach to burials with rolling hills and winding landscapes - this was in sharp contrast to the traditional orthodox B'nai Amoona. Chesed Shel Emeth at Hanley and Olive was opened in 1893 by Russian Orthodox. Latvian Jews opened Beth Hamedrosh Hagodol on Ladue Road in 1901 and Chevra Kadasha was opened on North and South Road in 1922. All of these Orthodox cemeteries were compact, crowded, but well cared for and strictly organized.

Early Burials

Prior to the civil war, enslaved African Americans were generally buried with the family who owned them. Slaves are mentioned in the records of many public and protestant cemeteries as well as in family graveyards. Free Blacks were generally buried in city-owned public cemeteries, potter's fields, or in Catholic cemeteries. Unfortunately, early burials were often marked with fieldstones, wooden headstones or crosses, or personal items - all of which have disappeared.

Church Cemeteries

There were many small African American church congregations that formed following emancipation and many of these churches had churchyards or cemeteries where they performed burials. As with early protestant and catholic parish cemeteries, funds for perpetual care were not set aside and because burials in these cemeteries were free - little care was performed. It was the responsibility of the families to maintain their loved one's graves.

Commercial Cemeteries

In 1874, Greenwood Cemetery opened on Lucas & Hunt near St. Peter's Cemetery. In 1903, Father Dickson cemetery was opened by the International Order of Twelve Knights and Daughters of Tabor on Sappington Road in Crestwood. In 1920, Andrew H. Watson opened Washington Park Cemetery on Natural Bridge Road. All three cemeteries were built in the rural cemetery tradition. However, unlike other rural cemeteries, no plans were established for perpetual care. In the 1970s, control of the cemeteries transferred to new owners. The new owners - discovering no funds for perpetual care - realized the only way to profit from the cemeteries was new burials. The cemeteries quick fell into disrepair and soon became overgrown, vulnerable to vandalism, and other illegal activities. Fortunately, in the 1990s concerns were raised and Greenwood Cemetery and Father Dickson Cemetery benefited from large scale volunteer restoration projects which continue to this day.

Washington Park's story is more tragic. Interstate 70 projects and airport expansion resulted in large removal projects at the cemetery with thousands of burials removed. Other burials bordering on the airport or interstate were flooded by water disposition from the new infrastructure projects. From September 1987-1989, new ownership did a particularly poor job of record-keeping, failing to record the section / lot / grave of a large number of burials. Today, the cemetery is in extremely poor condition despite multiple active efforts to save it. Large portions of the property are overgrown and impossible to venture into without significant clean-up. Burial markers are missing / damaged or completely lost to woods or water.

Early Burials

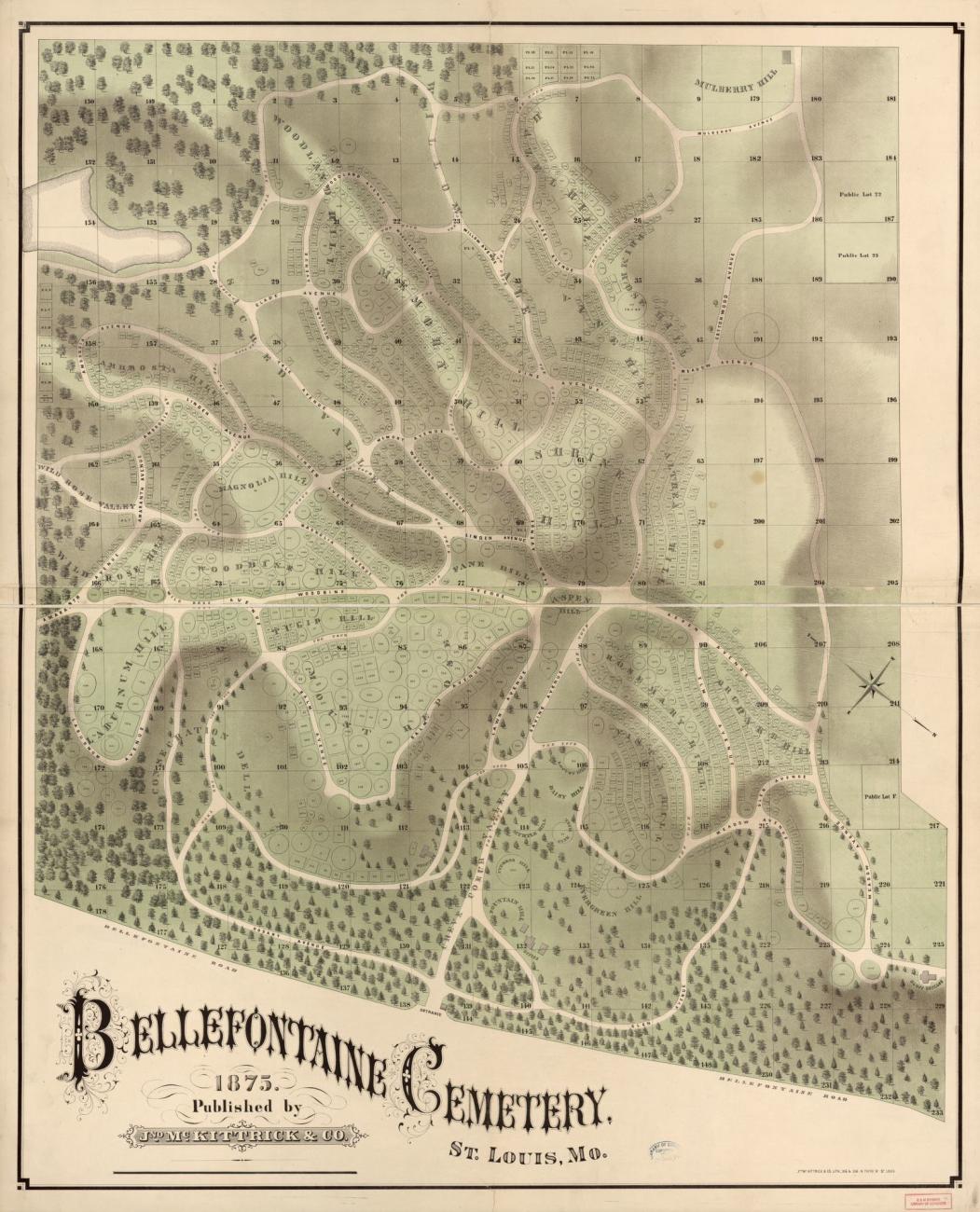

Many fraternal organizations established in St. Louis would provide members with burial and death benefits - including free burial spots for their members. Many organizations purchased burial plots in Bellefontaine Cemetery. In 1890, the Woodmen of the World ( established in Omaha, NE) guaranteed their members prepaid burials.

Fraternal Cemeteries

In 1877, the Deutsch Orden Harugari purchased two acres for members and their wives in Manchester. In 1884, the Arminia Lodge of Deutsch Orden Harugari purchased two acres on Olive Street Road for a meeting lodge and cemetery. Burials were probably free at both cemeteries. In 1881, the St. Louis lodges of Odd Fellows purchased five acres near Jefferson Barracks for a cemetery.

20th Century

St. Louis was an early adopter of commercial cemeteries featuring attractive elements of rural design that were streamlined for ease of care. Unlike traditional cemeteries, these commercial cemeteries could provide expanded services for a profit. The first of these cemeteries was Valhalla, established on St. Charles Rock Road in 1911. Valhalla was run by Charles B. Sims, a Chicago lawyer who had previously opened another for-profit cemetery in Mobile, AL in 1905. Sims' empire of cemeteries expanded in California, Alabama, Illinois, and Wisconsin. He also opened Mount Hope Cemetery in St. Louis County. In 1916, Hubert Eaton bought out Sims and hired Sidney Lovell to design the Valhalla Mausoleum. Lovell also designed Mausoleums at Mount Hope and Oak Grove cemeteries.

In the years prior to the Great Depression, investors inspired by Sims purchased large tracts of farm land for commercial cemeteries. Park Lawn (1912), Memorial Park (1919), Lakewood Park (1920), Washington Park (1922), Lake Charles (1922), Mount Lebanon (1925), Hiram [Bellerive] (1925) were all established during this time period. All of these cemeteries are rural movement inspired and many feature mausoleums which dramatically increase the capacity of the cemeteries.

Family Graveyards were a common practice of rural protestants of southern or midwestern heritage. As the local protestant churchyard or cemetery may have been a great distance from the family home, it was commonplace to bury several generations of loved ones in a cemetery plot on your families' land. Often these family plots contain several generations of family members as well as family slaves and freed blacks who lived near their former owners.

Family graveyards were once common across St. Louis County anywhere a family might have been isolated. As development pushed westward, many of the family plots have been exhumed and transferred to a protestant or community burial ground. Those family plots which remain mostly exist in rural western edge of St. Louis County in Wildwood, Ellisville, Chesterfield, and Eureka.

Books

-

At Rest in Wildwood

Call Number: R977.865 A861 -

Chesterfield, Missouri Cemeteries

Call Number: R 977.865 M575C

The St. Louis City [Mo.] Burial Certificates microfilm set at the St. Louis County Library History and Genealogy Department is comprised of 121 rolls dating from January 1882 to October 1908. Although most of the information on the Burial Certificate form is the same as that on the Death Register (see number 2 below), it is useful to double check difficult handwriting, fading, or poor microfilming in the Death Register.

The Burial Certificates were filmed by the Missouri State Archives and include only burials in the City of St. Louis. However, it is important to note that in some cases, the decedent died somewhere other than the City of St. Louis and was brought to St. Louis City for burial, thus requiring a St. Louis Burial Certificate. When a death occurred outside the City of St. Louis, look for documents filmed with the certificate that possibly provide information about the place, date, and cause of death.